On Estimates

Since we began developing software, we’ve looked for ways to reliably estimate our development time. Now, some 60+ years later, we’ve gotten no better at it. Maybe the problem is not in how we estimate, but that we’re so concerned with estimates in the first place.

Take the popular Scrum framework. At its core, Scrum is based on estimating the future work and taking only as much as you can supposedly do into the next sprint. At first glance, it sounds reasonable. In reality, more often than not, it means trading team performance for the illusion of planning. I’ll explain why.

Estimates slow us down

People naturally want to be good at what they’re doing. At first, developers tend to be optimistic, and accordingly tend to underestimate their task times. What inevitably happens next is they commit to the specific timeline that they themselves stated and fail. This makes them feel uncomfortable, even when no one blames them (and sometimes people do blame them). As the process repeats itself, they slowly learn to overestimate, because they don’t want to fail.

Counterintuitively, overestimating doesn’t always help people to finish their work on time. This effect is known as Parkinson’s Law, and here’s where psychology plays against us. Let’s say you think a task will take a couple of days, but, given the uncertainty, you might need up to a week. You estimate a week, and your manager says “fine.” Now you think - alright, I have plenty of time! As a result, in the first half of the week, you either work in a relaxed mode or shift your priorities to other tasks, because you know that you have plenty of time. As the timeline approaches, you start to realize that the task is not as simple as you’d initially thought and remember why you overestimated in the first place. So you work hard, maybe stay late, and finally, barely fit the work into the timeline you set for yourself. Next week, the same story happens again.

Ultimately, problems happen either way you estimate. If team members are under time pressure (often because they’ve underestimated), they may have to cut corners to meet the timeline. Surprisingly, if they overestimate, the same thing happens, just later. As a rule of thumb, you may think of deadlines as “the earliest dates when something can be delivered.” So no matter whether they over- or underestimated, nothing ships until the deadline.

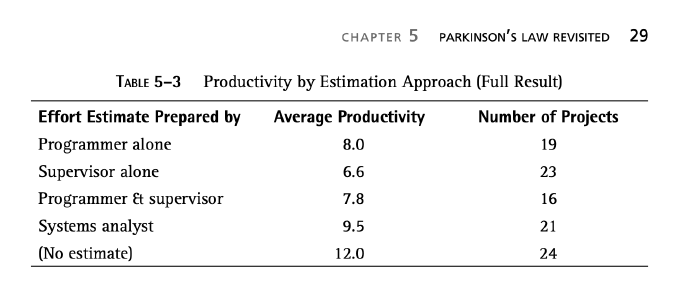

Source: Peopleware by Tom DeMarko and Timothy Lister

Estimates slow the team down, and the more frequently you ask developers for estimates, the worse the effect becomes. If a team estimates all the work it’s doing, then the amount of time and energy it must spend on the estimating process will be overwhelming. First, people spend time making the estimates. After that, they spend time discussing why those estimates failed and what they should do next (usually, the solution is to request more estimates.) Next, requirements change - and voila, now they have to figure out how the change affects their estimates. Finally, they deal with the technical debt accumulated in their numerous attempts to meet the estimated timelines, slowing the project down in the long term.

Quick estimates are just guessing

The nature of software development entails a lot of complexity and uncertainty. Almost all of the work that developers do is something new. Even if they’ve done something similar in the past, they’re now doing it in new conditions. There might be a new project, or new requirements, or new knowledge learned from the last experience. If it were absolutely the same and routinely repeated, it’d likely already be automated, or be implemented as an out-of-the-box product, or exist as a library or framework. Therefore, in most cases, developers have to provide estimates for tasks that have a high degree of uncertainty.

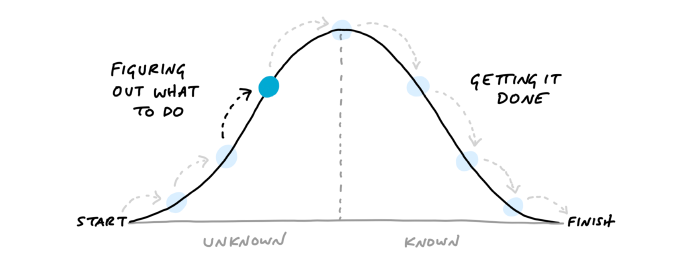

Source: Show Progress | Shape Up by BaseCamp

It could be better if developers are given some time to work on the problem in advance; in such cases, they would understand the problem better and be more confident providing an estimate. Unfortunately, it rarely happens in practice. Developers usually have very little time to study a problem before someone asks them for an estimate. As a result, they pluck numbers out of thin air.

Of course, all experienced managers know that estimates are just estimates and don’t try to treat them as hard deadlines. However, they are perceived as some form of commitment anyway, by both managers and developers. If estimates mean absolutely nothing, why ask for them in the first place? So providing an estimate means being accountable for it. It’s no surprise that developers often don’t like them - basically, we ask them to be accountable for something that they don’t fully understand.

Estimates create dangerous misconceptions

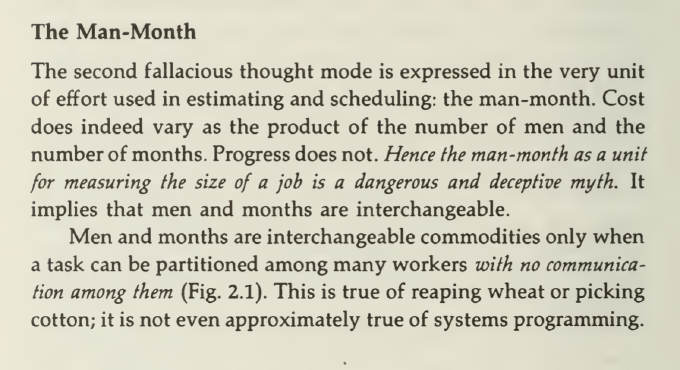

Uncertainty is not the only problem with estimates. They can also create misconceptions about the workflow for the project team and stakeholders. As Fred Brooks famously said, “The bearing of a child takes nine months, no matter how many women are assigned.” However, when people hear that a project will take nine man-months, they sometimes assume that it probably can be three months for three random developers.

Source: The Mythical Man-Month by Frederick P. Brooks

Men and months are not interchangeable, and not just because some work can’t be done in parallel. Who is doing the work also matters. A senior developer who’s also familiar with the matter could probably do it much faster than estimated, and a junior developer with no knowledge of the subject may not just miss the deadline, but fail the task altogether.

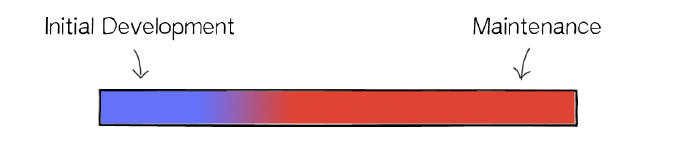

Initial development is a minor cost

Arguably the biggest problem with estimates is that people routinely ask for initial development estimates, but rarely ask for estimates about the subsequent maintenance. Maintenance is huge. It takes up to 60-90% of the total project cost. Besides that, every feature that you add to the product increases complexity and makes further development slower. With this fact in mind, people should be very cautious about adding new features. Instead, prioritize like a maniac, and work on only the features that make the most sense. This rarely happens when estimates drive project planning. In such projects, people tend to push features that take less time and postpone the ones that will take longer. As a consequence, the most important work can be postponed and the product becomes bloated with less important features and quick hacks.

How is it possible to plan a project without estimates?

Ok, so estimates take their toll. They can be misleading, they can slow a team down and make developers uncomfortable, but we need them for project planning anyway, right? Well, not necessarily. Sometimes estimates are unavoidable, but in most cases, they are not required for project decisions.

First, the initial development estimates shouldn’t be the driving factor that determines what to work on next. It would be best if you only worked on what is crucial, and not on what is fast to implement. If you’re not absolutely sure that a feature is essential, it shouldn’t be in the development queue. Use quick MVPs and product discovery to find out what your customers need.

Second, when you have a timeline to meet, communicate it to developers instead of asking for their estimates. There’s the excellent Fix Time and Budget, Flex Scope approach. Every task can be completed in thousands of ways. Prioritize the requirements carefully, work on the most critical items first, and be ready to ship at any time. In such conditions, timelines become manageable. Even if you’re not lucky enough to ship it fully, the most important features will be there and the least important will be missing, which quite often aren’t critical to launching.

Finally, if you badly need an estimate, give developers a few days to work on the task before asking. If you’re lucky, the task will already have been completed, and no estimate will be needed. Otherwise, they will understand the task better, and you’ll be able to have much more productive talk about the task challenges. Make sure that you take into account not only initial development estimates but also long-term maintenance, which is usually more important. And once again, if you’re not sure that the task is essential, it shouldn’t be in the development queue, even for estimates.

Managing expectations

This one is probably the most challenging. As a manager or a team lead, you will likely deal with stakeholders who will wonder how long a project will take. If you ask them why they need this information, they’ll tell you it’s necessary for planning or that they simply want to know what to expect. We discussed planning above, now let’s turn to expectations. It’s human nature to be concerned if something you care about is uncertain. It may be your boss who’s asking, and it may be hard to say, “I don’t know.” Here’s what you can try:

- if the work’s already in the queue or in progress, ask what plans related to the completion of this work. Try to help them execute their plans. Sometimes, you may use this information as an input for work prioritization and communicate their expectations to the team. Other times, you may find workarounds that would help those people to achieve their goals while the task’s still in progress;

- if the work is not in the development queue yet, ask about its priority. Talk about the plans that the development team already has, try to figure out where this new work can fit. Sometimes you’ll find there’s no chance that you’ll work on it anytime soon, and if so - there’s not much sense in discussing estimates;

- focus on team productivity and work transparency. If your team ships to production every day and everyone can see the work and the queue, people are less inclined to ask for estimates;

- as a manager or a team lead, track the progress of your team regularly. Know what was done and what’s remaining, what the blockers are, etc. If you know what’s going on, you can make your own estimates and communicate them to stakeholders when you think it’s necessary. Remember, good managers work as a “shit umbrella” for the team; bad managers let the shit fall through. Passing all requests for estimates down to developers is not good management practice.

Conclusion

To summarize, while estimates look appealing and straightforward on the surface, really they are misleading and obstructive to the workflow. It’s natural for humans to simplify complicated things, but estimates simplify the perception of the development process far beyond what’s reasonable. Scrum can take this over-simplification to the extreme with its planning poker, velocity, and burn-down charts.

Most people would agree that, though estimates are imperfect, they are at least measurable. They can’t imagine how to manage a project without having something measurable. Unfortunately, not everything that counts can be measured, and not everything that can be measured counts. In this post, I provided some practical advice from my experience of managing projects without estimates. Of course, I’m not saying that estimates are entirely useless; I’m just saying that most of the time, other more important factors should be at play. I’ve used this approach for years, and it’s worked well for our teams.

I realize that this advice is not for everyone. I worked with different organizations, big and small, and most of them used estimates in one form or another. At the same time, most organizations are far from efficient. The way the best teams operate is often different from the way the majority does. Perhaps the emphasis placed on estimates is one place where these differences lie.

That’s all I have for now. If you have any comments or questions - please feel free to reach me on Twitter. This post may be edited later if I have more thoughts on it. In such a case, the history will be available here on Github.

P.S. More on the topic: